Will Houston Flood Again in 2018

![]()

And the Waters Volition Prevail

What if Houston's survival depends not simply on withstanding a inundation, but on giving in to information technology?

Part i: Overflow

Dean Bixler used to go golfing near the summit of Brickhouse Gully, a neglected drainage canal, at a form chosen Pine Crest. It was near his firm in west Houston, and not a bad place to play until information technology closed downwardly a couple of years back. In the months after Hurricane Harvey, savoring his $30,000 floodproofing investment, including metal doors with gaskets that had kept h2o out of his house, Bixler heard from a neighbour that the golf grade was existence adult. The neighbor was concerned that the new subdivision would supplant depression-lying grass with roofs and roads and that the runoff would flood their neighborhood in a heavy rain. In Brooklyn or Boston, residents worry new neighbors will have their sunlight or their parking spaces. In Houston, the business organisation is new neighbors will bring flooding.

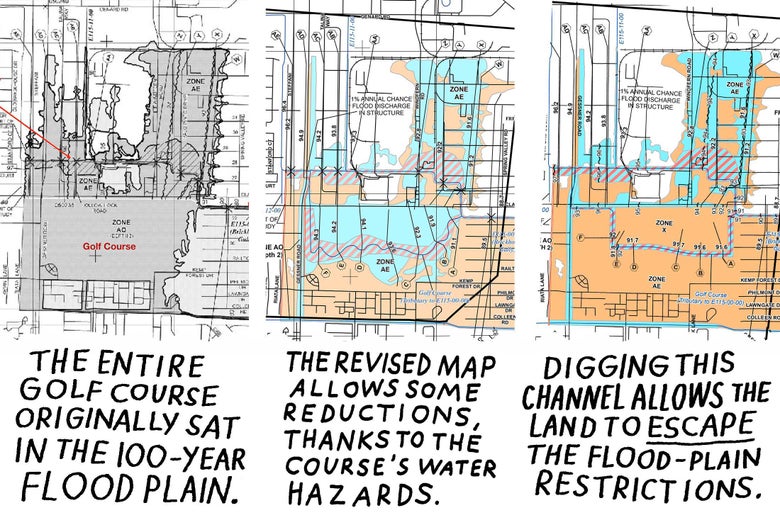

Bixler downloaded Federal Emergency Management Bureau maps and institute something strange. For the by decade, the entire course had sat in the 100-year flood plain—state, unremarkably virtually bodies of water, that has been assessed equally having a 1 percent chance of flooding every year. What that official designation ways is both practical take a chance to the homeowner and, for anyone with a Federal Housing Administration mortgage, a potentially onerous requirement to buy flood insurance. In most places in the U.S., a alluvion plain encompasses embankment houses and ribbons of properties along fast-ascension rivers. In Houston, the 100-year clings to the bayous, gullies, and ditches that give the city its natural graphic symbol and duck beneath the roads and lurk behind houses. On a map, the flood apparently is to the bayous as leafage is to a branching tree. The maps Bixler pulled indicated that, according to government-canonical estimates, Pino Crest golf game grade could be expected to sit beneath 2 feet of water during what would be called a 100-twelvemonth storm.

In a city locked in a mortal battle with h2o, that was no small thing: That much water spread beyond the form (at least briefly detained, in water-management lingo) would mean that much less h2o flowing immediately downstream in a big storm. The water from the course would flow into Brickhouse Gully, which would in plough rush east to empty into a bigger channel, the White Oak Bayou, forth which more than 8,000 houses were flooded during Harvey. Merely then Bixler saw the FEMA map had been revised once already, with a farther revision conditionally approved—substantially showing that as long equally the owner, a developer in Houston, dug a channel where the golf course'due south water hazards lined up, the whole property could gradually emerge from the FEMA danger zone. The 100-year flood evidently the grade sat upon would, as far equally the official map went, disappear.

At present the revisions made sense. The new owner, an Arizona homebuilder called Meritage Homes, could terraform the flood apparently into 100 acres of dry state fix for 900 houses selling for well-nigh $400,000 a slice. Judge revenue: $360 million. Homebuyers with FHA mortgages wouldn't exist required to buy flood insurance or grapple with the fears that come up with living on a inundation plain every time the heaven darkened. The new houses, perched on fill up more than 2 feet higher up the safer 500-twelvemonth flood mark, were expected to stay dry out in a major storm. But if the water that had once saturday on the golf class went downstream, where would it finish upwardly?

Houston is as flat every bit a tile, and most as resistant to water. It rains a lot (more than than it used to), and it rains hard (harder than earlier). H2o ripples beyond the fields of concrete and tends to menstruation correct over the raw earth, too, a clay mix chosen "black gumbo." Despite the all-time efforts of civil engineers, the natural streambeds that acquit water from the county line to Galveston Bay aren't much bigger than they were in 1950, when this was a city of 600,000. It'south grown fourfold since so.

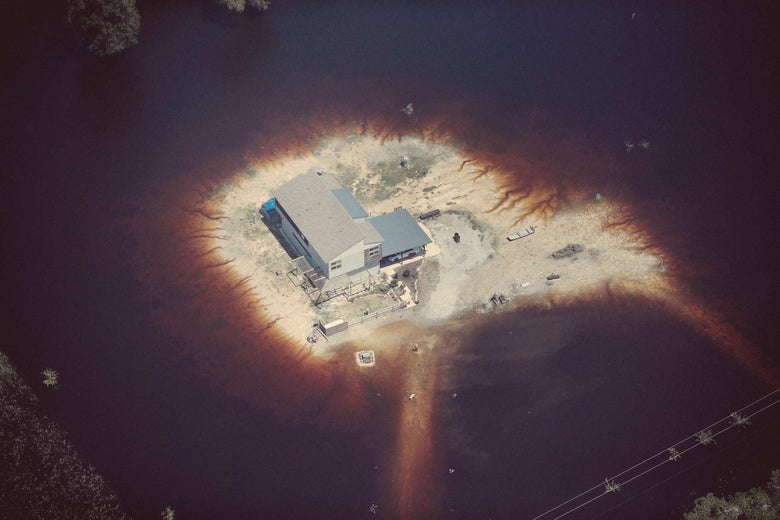

Unprecedented storms have brought 3 straight years of biblical floods, culminating in Harvey, which inundated 154,170 homes in Harris County—the Delaware-sized area that contains the metropolis of Houston and some other Houston'due south worth of people outside it. Most one-half of those houses were in neither the 100-year nor the 500-year FEMA flood plain. Why did they alluvion? In role considering Harvey was a leviathan of a tempest swollen past a carbon-thick atmosphere, a once-in-10,000-years rainfall event. The weight of the h2o flexed the world's crust and temporarily sank the city a one-half-inch. And the homes flooded in role because Houston, similar other cities, has reshaped its natural flood plains with concrete. Human construction at present decides where the floods go.

Bixler is tanned and stocky, with shut-cropped, thinning hair and a goatee. He used to work as a seismic engineer in oil and gas, and he brought a sheaf of printed maps and charts to a strip-mall Starbucks to demonstrate what he perceived every bit the dirty tricks that had been used to extract the class from the 100-year flood plain. "It'due south very clever engineering," he told me. In his white pickup, classic rock radio on the dial, nosotros cruised the roads around Pine Crest. It is hard to imagine a flood on a sunny mean solar day, just Bixler did his all-time to assist. Near the top of Brickhouse Gully, as nosotros looked down on a still pool teeming with turtles, he smoked a cigarette and reflected on his struggle to bring the development to a halt. "To be quite honest, I wish my neighbor had never shown me this. I've lost organized religion in the metropolis," he said. "It makes me ill that the people supposed to be protecting us, Harris Canton Flood Control, is helping these guys."

In November of final twelvemonth, shortly after Bixler dug up the flood maps, Meritage sought city blessing for a special tax district to develop Pine Crest. Two months after Harvey, the prospect of a flood-prone 18-hole golf class on the upper watershed being paved into a k driveways was treated as a scandal. The editorial board of the Houston Chronicle wrote, "Our city tin can no longer tolerate a borough philosophy that insists on construction at any cost. We can no longer allow developers to treat our city as their playground for turn a profit. … A natural sponge for floodwater would be transformed into a physical pipeline that drains right into Buffalo Bayou." And it was all happening along Brickhouse Gully, where, to avert future flood damage, the city had bought out 30 homes before Harvey and wanted to purchase 15 more than. At present, only uphill, information technology was enabling the construction of 900 more.

The outcry managed to postpone the vote, just little more—in April, the urban center gave the aforementioned proposal a unanimous go-ahead. Not everyone thought this was the best use of i of the largest remaining single infill parcels in the city. "If the Flood Control District had been able to purchase that state, I'd exist designing and planning to construct a large detention basin in that expanse," said Matt Zeve, the director of operations for the Harris County Inundation Control District. Past August, Pino Crest was well on its way to becoming Spring Brook Village, a projection that embodies the challenges that Houston faces every bit it confronts an existential question: Did the urban center build its way into cataclysm?

Part 2: Terraform

On Aug. 25—the one-year anniversary of Harvey's landfall—an astounding 85 percent of Harris County voters approved a $2.5 billion bond issue to fight flooding. Information technology's the largest bond issue in the history of Texas' largest county and, everyone agrees, long-awaited recognition of the dangers that Houston faces. The support is a attestation to how deep an impression the tempest has left; it will quadruple the Flood Control Commune's annual budget.

On a recent dark, a friend took me to a party in west Houston where an older couple was celebrating the motility back into their house, well-nigh a year after Buffalo Bayou came in through their dorsum door. It was a hot, notwithstanding night, but you couldn't hear the stream through the forest, let solitary encounter it—or, for that matter, imagine this group of older Houstonians in polo shirts launching kayaks out their garage doors, through brown water rushing in rapids over submerged pickup trucks.

Amidst the Harvey survivors I met were Patti and R.J. Simon; last August was the fifth time their ranch business firm on Brays Bayou had flooded. They waded to a neighbour's elevated dwelling house. Then they finally moved. At 75, Patti told me she was done with the routine that had accompanied the years in their house since Tropical Storm Allison in 2001. Washed putting the burrow up on the kitchen counter each time they saw a bad forecast—and too old for it besides. And so they left the neighborhood they'd known for decades, where Patti could walk to her job teaching French at the loftier school, and friends from church could come by and help move the boxes in and out every time the water came in the door. They lost the door frame where they measured the kids. This wasn't their children'due south chief concern. "They would accept committed us to aviary had we stayed," she said. Harvey was their 3rd flood in iii years.

The Simons aren't solitary: Homes that once flooded rarely, if ever, are suddenly flooding more. The overflowing plains are on the march, creeping inland from surging bayous. All three of the conduits beneath Pine Crest—Brickhouse to White Oak to Buffalo, a double-play combination that drains this stretch of northwest Houston—are amongst the 12 fastest-rising urban waterways in the state of Texas. Since records began more than than 50 years ago, Buffalo Bayou's peak flows are upwardly 250 percentage. Brickhouse Gully's peak is upwardly about 400 percent. And White Oak Bayou, over a slightly longer time frame, is up nearly 600 percent. That doesn't include Harvey, said watershed scientist and consultant Matthew Berg, who published the information. "Pretty much all the fourth dimension, evolution is a slice of it," he asserted. "Information technology's just a question of how much." Two in three Houstonians believe lax regulations have made the metropolis's flooding bug worse.

Dean Bixler is one of them. The house where he and his wife live was congenital in 1960. It has now flooded 3 times, all in the past decade. What changed? He pointed to a behemothic, raised shopping center up the colina. Information technology'due south hard to bear witness these things, but Bixler felt information technology was obvious: The projection had displaced scores of acre-anxiety (an acre-foot is an acre of water, 1 foot deep), some of which had wound up in his living room. Three times in 10 years. He lost two cars, and, similar many people in Houston, he has learned to park up the block, on higher footing. (A joke I heard, which might not be a joke, was that the highest points in Houston are the soaring ramps of highway interchanges.)

Bixler saw in the Pine Crest evolution a supercharged version of his domestic battle. It wasn't even in his watershed. Merely with 900 homes on a little more than 100 acres, Pino Crest was to be among the largest infill projects in the city of Houston, an irresistible morsel for builders and a red flag for wary residents. A Meritage executive said last spring to the Houston Business Journal, "What we saw was the biggest opportunity available in the urban center in terms of one tract of land."

Members of Residents Against Flooding, including Bixler, allege that the map revisions distort how and where the water flows. The revisions were prepared by local hydrological engineers working for the site'south previous owners, MetroNational, and certified past the Harris County Flood Control District on behalf of FEMA. The 2007 map shows the golf game course could be under roughly 200 acre-anxiety of water during a 100-year storm; equally the developers carve a channel through the property, removing the banks from the 100-yr overflowing obviously, some of that water appears to get missing.

The course has been closed for simply a couple of years, but in the tropical climate it has rapidly reverted to nature, with black-eyed Susans and dumbo scrub filling the fairways between stands of pine. Information technology won't be wild for long. At the low end is the wide grass halfpipe that will one day funnel runoff from 900 driveways into Brickhouse Gully, role of what Meritage says will exist a state-of-the-art drainage-and-detention organisation that will actually improve conditions downstream relative to the sometime golf grade. On sunny days, information technology volition double as a lovely water feature along which residents can walk their dogs and ride bicycles. To pay for information technology and other improvements, Meritage got the city to approve a "special utility district," a geographic taxation cess that will allow a $280 one thousand thousand infrastructure bond upshot to be paid off through buyers' futurity property taxation bills. (It'due south a way to pass costs onto buyers.) At the loftier cease, the copse have been felled, and grassless fill rises from the street to escape the 500-yr flood mark. Ii-story homes, modest and with lilliputian flair, are open for tours.

The Harris County Inundation Command District, for its function, has looked into all of this at the behest of Residents Against Flooding and stands by its certification of the work by the developers' engineers. According to Todd Ward, a risk specialist and hydrologist at the Inundation Control Commune, the revisions are just more than accurate than the maps from 2007. (After complaints, the agency did its own analysis to verify this.) "When y'all look at it in more detail, you find at that place's a lot more high basis than you might recollect. The actual volume stored on the site is quite a bit less than [what the 2007 map implies]." The new channel would exist deep enough to bring the adjoining land safely out of the 100-year overflowing plain. The agency too promises that the Meritage evolution plan will have "no adverse impact" on water levels downstream, meaning that any flooding should exist the same or less than if the evolution weren't in that location.

In normal times, the complaints of neighborhood cranks might not be worth much against the give-and-take of the county's hydrological authorities. But confidence in local water guardians is not high. Thousands of plaintiffs whose houses flooded during Harvey have filed suit against the Army Corps of Engineers, which runs the urban center's two giant dams, for flooding their homes without alert past releasing water from the reservoirs as they neared capacity.

Meanwhile, the Harris County Overflowing Command District insists that the past three decades of new development have not acquired more flooding—a view that is non widely shared. "People have always said the guy upstream of me is making me overflowing," Zeve, of the Alluvion Command District, told me. "That has been a mutual theme throughout Houston history and e'er will be. No one is going to deny that development increases the volume of water, only detention regulates the tiptop catamenia." Non just in theory: Zeve said the agency's watchful eye has successfully mitigated the effects of new development since the early 1990s. To testify it, the agency has commissioned a peer-reviewed investigation of its own detention requirements (otherwise, he notes with some self-awareness, no one would believe them), and preliminary results suggest their requirements are effective. The urban center's recurring overflowing issues, he argued, can exist attributed to huge storms hitting a city largely built earlier anyone knew what a flood obviously was.

Several experts I spoke to plant that proffer—that new evolution was not having an event on flooding—ridiculous. As Houston has sprawled westward over the Katy Prairie, 75 percent of its overflowing-absorptive grasslands have been paved over, turning natural detention basins into roads and houses. In Brays Bayou, on the south side of the metropolis, Rice environmental engineering science professor Philip Bedient has found that rainfall is upward 26 per centum over the past 40 years—only runoff is up 204 percent. From 1996 to 2011, impervious surface in Harris County increased past a quarter, and from 1992 to 2010, the surface area lost almost a tertiary of its wetlands—near xvi,000 acres. Information technology's a correlation that's been noted again and over again. "There'south no question that the corporeality of impervious surface and the destruction of natural ecosystem surfaces has impacted the corporeality of runoff and flooding that we have seen," said Shannon Van Zandt, the head of the landscape architecture and urban planning department at Texas A&Chiliad. "There'southward no question about that. I don't retrieve information technology's plausible to suggest that the detention is taking intendance of the issue."

Critics say the arrangement is built to corroborate more housing, non deliver objective science. Engineers who sign off on developments, assuring the public they will not contribute to flooding, bid for work from developers, who hire engineers who can brand things pencil out. Those houses within the dam basins whose owners are suing the Army Corps? Certification work for some of those projects was washed past an engineering science firm run by Houston's current flood czar, Steve Costello. His firm was so deep in the merchandise that, when later elected councilman, he had to recuse himself "from more than 60 matters involving his house, including city alluvion-control contracts and reviews of municipal utility district deals spread across the region," according to an investigation in the Houston Relate.

Jim Blackburn, an environmental lawyer and professor in the Rice Department of Ceremonious and Environmental Engineering science, thinks the county must detect a way to end this cozy relationship betwixt engineers and their dual masters, developers and (according to state licensing) the public. One footstep would be to prohibit the types of flood plain map revisions that the developers had undertaken at Pino Crest. So some. "Every bit far equally I'm concerned, Pine Crest proves the larger point, that we don't have proper respect for the inundation plain. Nosotros're going to have to turn land over to water. Water volition demand infinite in this city whether we like it or not."

Role three: Progress

Judge Ed Emmett, the chief executive of Harris Canton and most powerful politician in the region, agrees: "Nosotros're non going to build our manner out of this problem." The saga over the evolution of Pine Crest is a Houston city issue, Emmett emphasized, just he said candidly: "It has been a mess."

In the yr since Harvey, the Republican has emerged as a born-once again advocate for better flood command. He said Harris County has the strictest building codes and flood plain regulations in the country. It was his decision to schedule the bond issue for the one-yr anniversary of Harvey. "When was the last time you saw 85 percent for anything?" he asked the oversupply at a supporters' gathering Sat dark. He's criticized the way development was conducted for decades (some of it on his watch). Though a champion of the Grand Parkway, the outermost western beltway nether construction, Emmett talked conservation at a forum in February: "Nosotros demand to completely protect the Katy Prairie," he said of the groovy plain in western Harris County. "Simply set it bated and not touch it."

There are signs of awakening in the urban center, also. Kickoff Harris County, and so Houston, mandated that all structures in the 500-yr flood plain must be built 2 feet above the base alluvion elevation. The "zero net fill up" rule forces all 500-year alluvion plain builders to dig an equivalent pigsty for every hill they construct. That'south among the strictest metropolis building codes in the nation, in a place so famous for freewheeling structure that the British architecture critic Reyner Banham compared it to "a real-life Monopoly game." It's a recognition that, on this coastal plain, deep into the Anthropocene era, the FEMA maps no longer accurately describe what happens on the ground. (When FEMA updates its maps, the city will revisit those superlative rules.) During Harvey, Houston buildings in the 500-year inundation plain were damaged at a slightly college rate than those in the 100-year flood plain. Now the city has substantially quashed the distinction.

"Of all the flood disasters I've lived through, this one seems to be creating more change than in the past," said Sam Brody, a planner who served on the National Academy of Sciences committee on urban flooding in the United states. Two feet at the 500-year level was not even on the table final year. "I was saying 2 feet freeboard at the 100-twelvemonth level a twelvemonth ago and people were saying, 'You lot crazy academic, that'south never going to happen.' "

The homebuilders got their concessions, though. Rather than force builders to elevate structures to a higher place the flood line on stilts, the urban center permitted slab foundations on raised, compacted soil so long every bit the builder could demonstrate water flows didn't change. This is a good thing, argues Marvin Odum, the one-time president of Shell Oil who was appointed Houston's primary recovery officeholder afterwards Harvey. "You lot basically take free rein as long as you don't alter how water moves off of that property," he said.

That'south how Meritage is doing it: houses on mounds, non stilts. While Meritage says all that fill up is coming from excavation out the property, it's non obligated to practice and then under pre-Harvey 500-twelvemonth requirements. Before the programmer received its April go-ahead to create its utility commune, the visitor did extensive outreach with the city quango and residents downstream, according to Robert Moore, a vice president of land development at Meritage. "They should feel bodacious," he said, "because it's been checked, double-checked, triple-checked to brand sure we aren't going to have a negative impact on them at all." Meritage says—and the Alluvion Command District agrees—that with the carved-out aqueduct and associated ponds, the development will hold more water upstream than the golf game course did. The company also suggested that the drainage work it had done before Harvey might have alleviated flooding on Brickhouse Gully, where 2,300 homes were inundated final August.

On blessing the utility district, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner cited the Meritage project as proof that the city's new code would not scare off the homebuilders who take fabricated the Bayou City a uniquely affordable American metropolis.

The chief risk facing Houston and Harris County is not the vulnerability of new developments, which exercise tend to be built higher, improve, and upstream, merely that of the older houses downstream, many built depression to the ground and served by undersized storm drains. It may not be the instance that your new neighbour upstream is making you inundation. But the standards could be higher. Activists say the choice between an abased, inundation-prone golf course and a subdivision of 900 homes was a fake one. Susan Chadwick, the executive managing director of Salve Buffalo Bayou, a grouping that opposes development in and around the river, argued in June that the city should have used eminent domain on the course to create a detention pond that would relieve Brickhouse Gully.

The engineers at the Overflowing Control District don't disagree it would have been a good place for a pool. As we saturday in his role going over flood plains, Todd Ward conceded information technology was a bit of a missed opportunity. We found the course on an enormous satellite map of Houston on the wall. In a behemothic city, it's a pocket-size square. Only there aren't many undeveloped parcels of that size left. Some of the but-canonical $2.5 billion bond volition get toward buying out existing echo-flooding homes downstream of the newly elevated houses at Leap Beck Village. The bond calls for $35 meg of channel improvements to Brickhouse Gully to reduce the risk to 1,300 homes.

No thing how much care is put into terraforming, the development will dump more water into the flooded channels than it would had it go a giant detention pond instead. "Yous can literally measure this thing in gallons going into someone'south living room," said Albert Pope, a professor of architecture at Rice. "There's a mode to become to fewer gallons." Pope is i of a growing number of architects, planners, and engineers who fence for an anti-flooding plan that looks not only at what will be congenital (edifice codes, detention requirements) simply too at what has been built. Those downstream residents are victims. They're also function of the problem. He is working on a blueprint for a phased retreat of the 100,000 Houston structures that lie within the urban center's 100-year flood plain. The bail was a good sign. But he added, "We are close to the end of engineering fixes."

To John Jacob, a wetland scientist and manager of the Texas Coastal Watershed Program, Houston'due south long-term strategy must simply be to evacuate the 100-yr alluvion evidently. It's the equivalent of demolishing a midsize American city. "It would exist traumatic. It's not something that should be taken quickly. But it ought to be a goal." He believes that the urban center'due south bayous, if restored to their total tempest-surge size and shorn of encroaching roads and houses, take the capacity to handle another Harvey. That country could be appropriated as a serial of linear green spaces akin to D.C.'s Rock Creek Park, with trails, fields, gardens, and paths. It'southward an enhanced version of the city'southward Bayou Greenways 2020 projection, a $220 one thousand thousand investment to assemble a 150-mile network of hiking and biking trails. Houston is non a walkable city, simply on the trail that winds along White Oak Bayou, cyclists and joggers share space in the sunken green curve of the floodway. Egrets alight by the water. It's a glimpse of a Houston where the bayou is something to be loved, not feared.

Source: https://slate.com/business/2018/08/houston-one-year-after-hurricane-harvey-is-at-a-crossroads.html

0 Response to "Will Houston Flood Again in 2018"

Post a Comment